Fugetsu-Do’s Brian Kito

In 1903, confectioner Brian Kito’s family opened Fugetsu-Do Sweet Shop in the Little Tokyo enclave in Los Angeles, California. Just like the neighborhood, Fugetsu-Do endured the forced relocation of Japanese-Americans during World War II, the 1992 Los Angeles riots, and economic downturns. The shop’s struggles and, ultimately, its survival reflect the story of Little Tokyo as a whole.

In 1903, confectioner Brian Kito’s family opened Fugetsu-Do Sweet Shop in the Little Tokyo enclave in Los Angeles, California. Just like the neighborhood, Fugetsu-Do endured the forced relocation of Japanese-Americans during World War II, the 1992 Los Angeles riots, and economic downturns. The shop’s struggles and, ultimately, its survival reflect the story of Little Tokyo as a whole.

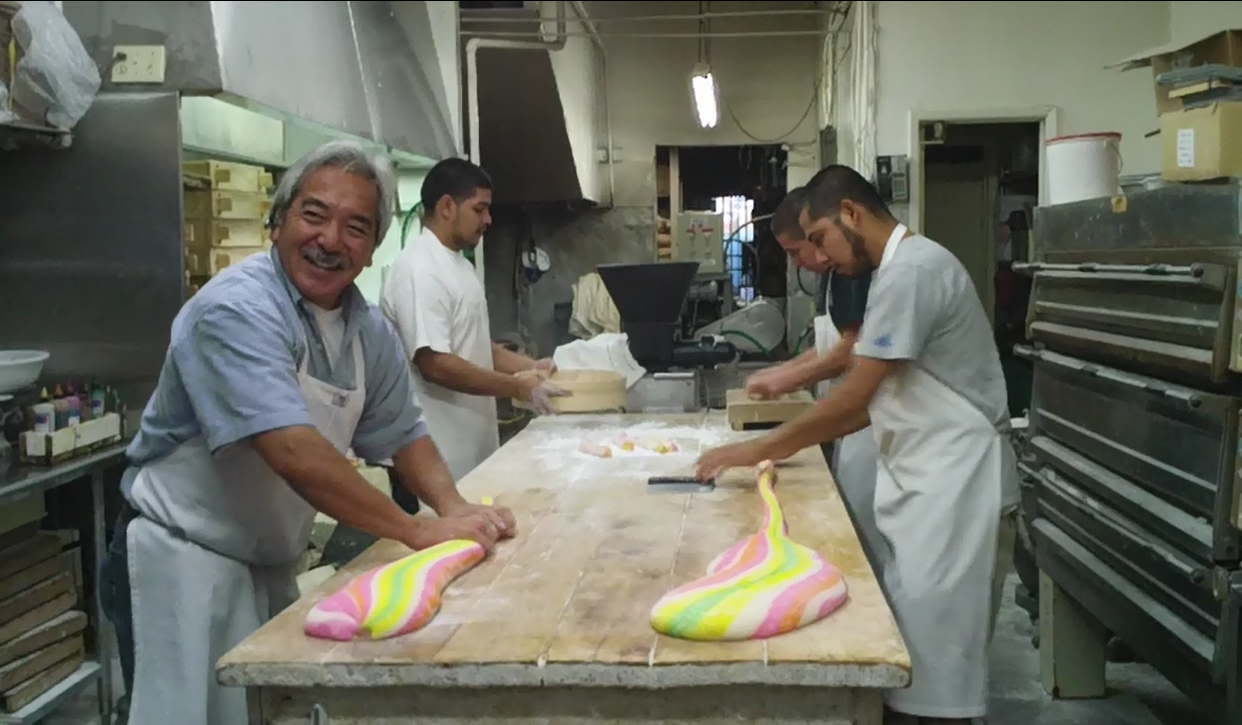

Fugetsu-Do is well known for its mochi and manju, traditional Japanese confections made of pounded rice. We recently visited Brian Kito at his homey shop and talked about the store’s cultural connection with the Japanese-American community over the past 116 years.

Fugetsu-Do is well known for its mochi and manju, traditional Japanese confections made of pounded rice. We recently visited Brian Kito at his homey shop and talked about the store’s cultural connection with the Japanese-American community over the past 116 years.

What does the name Fugetsu-Do mean? The name is kind of synonymous with Japanese confection because there are many stores in Japan with the same name, Fugetsu-Do. In Tokyo, they’ll say “Tokyo Fugetsu-Do” or there will be another prefix before it to tell which shop is being referred to.

Yours is the oldest sweet shop in Los Angeles. We’d love to learn some of its history. My grandfather, Seiichi Kito, was a confectioner in Japan. He and my grandmother, Tei, had sort of a Romeo and Juliet story of forbidden love. You see, when Seiichi fell in love with Tei, he was just an apprentice at a Japanese fugetsu-do. Her family did not approve of my grandmother marrying a man with such a lowly job so they decided to start a new life in the United States, where they had some relatives who were building a successful community. So, they came to Little Tokyo in 1903.

He opened Fugetsu-Do with some friends, making and delivering mochi and manju to the 3,000 Japanese people who lived here. The business was a lot of work, and all of the family worked together. Fugetsu-Do became more successful as Little Tokyo grew as the cultural and economic center of Japanese-Americans. Mochi and manju are important traditional Japanese foods for celebrations, funerals, and gifts. During certain holidays, it was so busy they had to rope off the front door.

In 1921, my grandmother died, leaving behind eight children. Her youngest son, Roy, was a one-year-old. Roy is my father. My grandfather could not take care of all of the kids, so he sent some back to Japan to be raised by family and friends. The baby, Roy, was sent to Japan.

Roy came back to Little Tokyo in 1935. He spoke only Japanese but learned English at the high school. He also worked at Fugetsu-Do. Six years later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. President Roosevelt then signed Executive Order 9066, forcing Japanese-Americans to be evacuated. My family and everybody else in Little Tokyo had between four days to two weeks to sell everything they owned. People from all over Los Angeles quickly heard the Japanese-Americans were being forced to sell their equipment and belongings for cheap prices, and they came to Little Tokyo offering five cents on the dollar for equipment because they knew there was really no choice for the Japanese-Americans.

My family was sent to Heart Mountain in Wyoming, an internment camp. While at the camp, other detainees gave my grandfather their sugar rations so that he could make mochi for them. My father met and married my mother in the camp.

After World War II, my grandfather and my father returned to Little Tokyo to rebuild Fugetsu-Do. Some of the items which were not sold were in storage, but the owner of the storage facility kept the machinery because my family could not afford to pay him four years’ back rent. With no home of their own, my family slept at Koyasan Temple. My father worked as a waiter for 20 cents an hour to save money enough to reopen the store. With the financial help and other support from the members of the Little Tokyo community, Fugetsu-Do reopened on Boy’s Day, May 5, 1946. About 10 years later, the store had to relocate for a couple of years when the building was demolished but it is now back in its original location. When the store moved back in 1957, my father became the sole owner. In 1980, I told my dad that I would take over the business. I’ve been the owner since 1986.

What an amazing story of resilience. Yes, there were a lot of struggles. Not only for our store but for the community, too. But knowing the history and everything that has transpired in Little Tokyo gives us a better understanding of the importance of this community.

You’re the third generation running Fugetsu-Do. What does the fourth generation look like? My son! But he is only 14.

Do you see him up next? He says, but I don’t know what a 14-year-old knows yet. He has hand skills, and that’s a good thing. When people come to work here, I know. They have to have some basic hand skill. So, I don’t doubt my son can do it, if he wants to. The question is whether he is going to want to later.

You grew up in this community. In fact, it sounds like you grew up in this store. What was that like? So, you grow up in this business and you know that Christmas vacation is not your time to take off. In college, most of my friends were going skiing or with their family somewhere. Our thing here was that vacation was a time to work. I’ve been here for Christmas for as long as I can remember, even sleeping in back. The whole family was here. Growing up, we had relatives here, uncles and aunts, everybody showing up to help.

Before the 1992 riots and in my grandfather and father’s days, since they were the first mochi store, people would line up outside during the holidays. If you didn’t order in time, you didn’t get it. There was just no way to produce enough mochi to meet the demand even though the family worked 24 hours a day for three days straight during the New Year’s holiday.

Do the different generations still work together like that? During the New Year’s rush, cousins send their children to work here. It is like a rite of passage. The younger generation experiences what the older generations did and we have a common thread that ties all of our family together.

What is this New Year’s rush about? On New Year’s Day, the Japanese eat a traditional mochi soup for good luck. The mochi soup has been the first thing in my mouth for as long as I can remember. It is a tradition, and we are one of only, maybe, three makers in the United States of the special mochi dumpling. Although we are a small little shop, we are, by far, the largest maker. We have to gear up. We drop all other production for the last four days of the year, and all we make is this one mochi dumpling.

What’s that mochi like? It’s a plain mochi dumpling. It has no sugar. It’s called komochi.

Does the kitchen at Fugetsu-Do still work 24 hours during this time? Yes. Because demand is so high, we go through 20,000 pounds of rice in the days leading up to New Year’s Day. Production starts going up right after Christmas, and it peaks on the 30th and 31st. The 30th and 31st is double what the 29th is.

Is it all family helping? No. We have some employees and family does help, but a lot of it is done by a group of volunteers. I do a lot of community work, so what happens is that a lot of people show their appreciation by coming to our aid during this time of year. They’ll come in at 2:00 a.m. and do a four-hour shift. It’s great. It’s a nice feeling. You get a lot of community feeling in here because that’s how it’s always been. It’s rejuvenating. It’s rejuvenated this store because in the last 10 years it’s become a community center but it’s my business — that’s the really different thing. The non-profit stuff I do is for non-profits, but this is my business so I feel a bit different about all the people who come in to volunteer. I have to repay that, somehow. So, usually, it happens during the year — not that I’m repaying them, it’s like they are repaying me and want this business to stay alive.

Have there been times when you doubted whether the business would stay alive? On our 90th anniversary, I almost closed the store. That was 1993. We were at rock bottom. Up until about six years ago, business was really tough.

What went wrong? After the ‘92 riots, Little Tokyo started to die. After the riots, nobody wanted to be down here. A lot of businesses disappeared. Japanese-Americans were moving out of Little Tokyo and they were not observing the Japanese traditions, so the business had fewer customers. As the Japanese-Americans started to assimilate and adopt American customs, we had fewer orders for traditional items such as wedding and funeral mochi and manju, which were a mainstay for my grandfather and father.

We also had some issues where the homeless population back in the mid-90s took over the streets. The panhandlers were extremely aggressive. Crime was a very big problem. It was almost blighted. I was the last business on this half of the block at one point. At night, you could come to First Street and mine was the only light you would see.

But before I gave up on 90 years of history, I started the Little Tokyo Anti-Crime Committee. For about 15 years, I donated my life to security issues. I quit all the other organizations at that time because I felt it made no sense to promote the area if you can’t keep it clean. You don’t invite people to your house when it’s a mess. I felt the same way about our community in the mid-90s.

When did things start to turn around? For the community, we knew that this area would never be successful again until we got a hold of security down here. That is where I spent a lot of my time, along with many volunteers and the LAPD. It is on-going. Now I am the President of our Historic Cultural Neighborhood Council. I am working to organize the community into getting a little bit better in marketing Little Tokyo. We are succeeding because Little Tokyo is one of the nicest places in the Downtown area. It didn’t happen by accident. It happened with a goal in mind.

When did things start to turn around? For the community, we knew that this area would never be successful again until we got a hold of security down here. That is where I spent a lot of my time, along with many volunteers and the LAPD. It is on-going. Now I am the President of our Historic Cultural Neighborhood Council. I am working to organize the community into getting a little bit better in marketing Little Tokyo. We are succeeding because Little Tokyo is one of the nicest places in the Downtown area. It didn’t happen by accident. It happened with a goal in mind.

For the store, I’ve made changes over the last 10 to 15 years to extend the product life cycle. For example, we made mochi bits for frozen yogurt during the frozen yogurt craze about six years ago. Right when the economy took its big downfall, I started the product. They were little squares that you could put on top of yogurt. We were lucky to have that product. Our sales started going back up and they are still going up. Obviously, everybody knows about mochi ice cream, but this frozen yogurt thing kind of introduced it beyond California into other states. I used to ship those mochi bits to almost every state. It’s amazing — even in Kansas City. How many Japanese are in Kansas City? Very few, but it is not just Japanese who were eating it. It’s crossed into the mainstream.

Have you also introduced new flavors to appeal to this new, broader market? Chocolate mochi. Peanut butter and strawberry mochi.

Strawberry and peanut butter? That’s an interesting combination. It’s strawberry flavored mochi with peanut butter. Take a bite, and what do you think of? Peanut butter and jelly sandwich. To tell you the truth, Japanese people are not real fond of it. They don’t grow up eating peanut butter and jelly, but the non-Japanese love it. It took off with the Americans, right off the bat. It actually started in Hawaii with peanut butter mochi. I added the strawberry flavor to the mochi, which adds the pink color and is aesthetically more attractive. Also, the taste of the strawberry. On the first bite, you taste the strawberry but, after that, it’s gone. Then you only taste the peanut butter. But, that initial bite gives you that strawberry.

You’ve updated some of your sweets offerings but you’ve resisted updating the store, which is lovely by the way. The store brings memories over generations. (Showing a picture) This bride took her wedding pictures here. She used to come here with her grandmother when she was little so she wanted to take her wedding picture here as a tribute to her grandmother.

I thought at some point to remodel the store but people come in, and they may have moved away and they are coming back to Little Tokyo after 25 years, and they see the store is still the same and tears come to their eyes. They say, “It is exactly the way I remember it.” They tell me they see this store and they recall the days of their childhood and their long-departed relatives. I respect the memories of all those kids that are my age who have something in this world that has not changed.

Besides, the new customers don’t seem to mind that it looks nostalgic. It is beat up but it has that finished look to it.

Fugetsu-Do Sweet Shop is located at 315 East First Street, Los Angeles, California. Visit them online here.

Share:

Comments

3 Responses to Fugetsu-Do’s Brian Kito